About 3 weeks ago, I was jolted awake by the incessant pinging of my phone.

It eagerly reported my low step count from the previous day, a flurry of linkedIn newsletters promising AI tools that’ll “10x my productivity”, and a mindfulness app prodding me to stay in the present moment.

All before I had a chance to rub my eyes.

I laid in bed shouting at my phone to **** off, flicked the ringer off, shoved it under my pillow and fell back “asleep”. Maybe you can guess what happened next, but my digital detox lasted about 10 minutes. Like an addict seeking a fix, I was wide awake and found myself reluctantly scrolling through my phone to make sure I was “up to date”, whatever that meant.

The rest of my morning went terribly.

As I reflected on my dependence on my phone, I realized we’re living in the midst of what Evan Armstrong coins as the 'addiction economy.' The addiction economy describes an insidious shift in modern living where the value of a product isn’t determined by its inherent quality or usefulness but by its ability to capture and retain our attention.

If you aren’t paying for the product, you are the product- Andrew Lewis

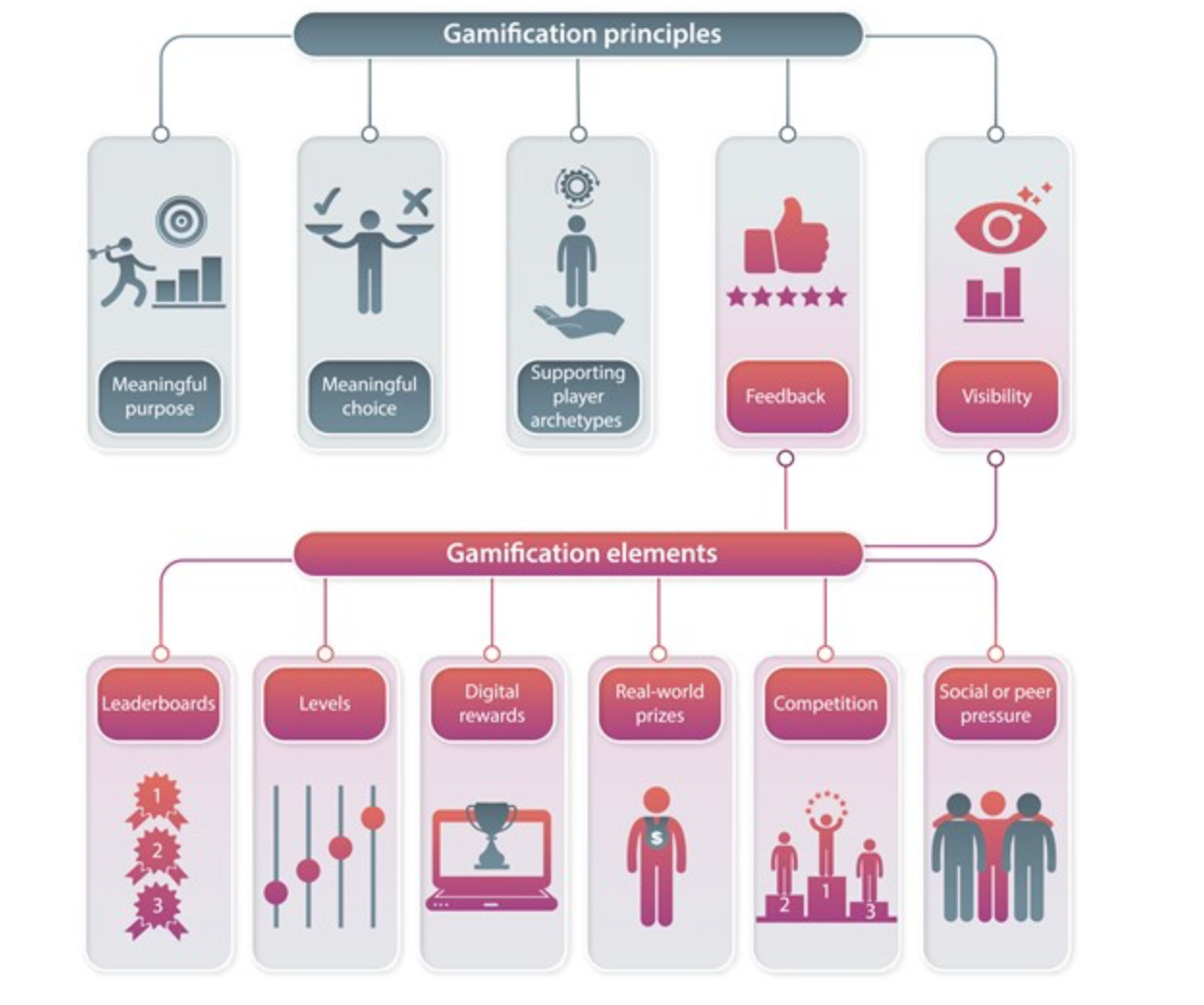

Everywhere I looked, I began noticing how consumer attention has superseded money to become the most valuable currency of the digital age. This isn’t accidental. It’s a result of carefully designed strategies employed by digital platforms using gamification, a method borrowed from video games that’s designed to keep users coming back again and again.

The hook of the digital age

Our favourite apps like Tiktok, Snapchat and Duolingo use gamification to keep users hooked on the platform.

And it works. The average TikTok user spends 95 minutes of their day on the app, or in other words, 2.3 years of their entire lifetime on TikTok. Mind-boggling.

Now, the addiction economy is making space for a new market.

Digital Health.

There are well over 350,000 digital health apps on the market place today, and an increasing number of those apps are using some form of gamification to try and motivate healthy behaviour change.

But can it?

While many academics believe “gamifying” healthcare will lead to long-lasting healthy behaviour change, I disagree.

I believe gamified principles in digital health apps leads to a superficial focus on extrinsic motivation that’s very good in keeping us engaged and addicted, but not very good at the meaningful behaviour change part.

Why? Because it’s almost like teaching a child to play the piano by offering them a piece of chocolate for every note they play correctly. Initially, they’ll be eager to play, hitting the right notes to earn a reward.

However, the child’s motivation is purely extrinsic and is driven by something at the end of it.

If we remove the chocolate, the child has very little incentive to continue playing.

Likewise, “gamifying” digital health apps using streaks, points, and rewards may initially be engaging, but once the novelty wears off, there’s a high risk the user reverts back to their original behaviour.

Because fundamentally, the goal of a gamified digital health app is to increase usage and engagement through extrinsic motivating factors, like all the other apps in the addiction economy.

And this won’t lead to healthy behaviour change, no matter how many 'pieces of chocolate'—or digital rewards—are dangled in front of us.

Let’s take a look at a real example that happened to me a couple of weeks ago using the popular mindfulness app headspace.

My Rollercoaster Ride with Gamified Zen

I’ve wanted to build a mindful meditation practice for a long time now because I genuinely enjoy the peace, clarity and sense of gratefulness it brings me. In other words, a behaviour change theorist would say I am intrinsically motivated to practise mindful meditation.

However, in reality, intrinsic motivation isn't always easy to act upon. Even if I’m intrinsically motivated to meditate, there have been considerable hurdles to overcome in reaching my goal and my motivation has wavered a lot over the past few months.

In contrast, extrinsic motivation hinges on rewards for task completion. These immediate incentives can powerfully drive short-term engagement and performance. Like the example of the child playing piano for chocolate.

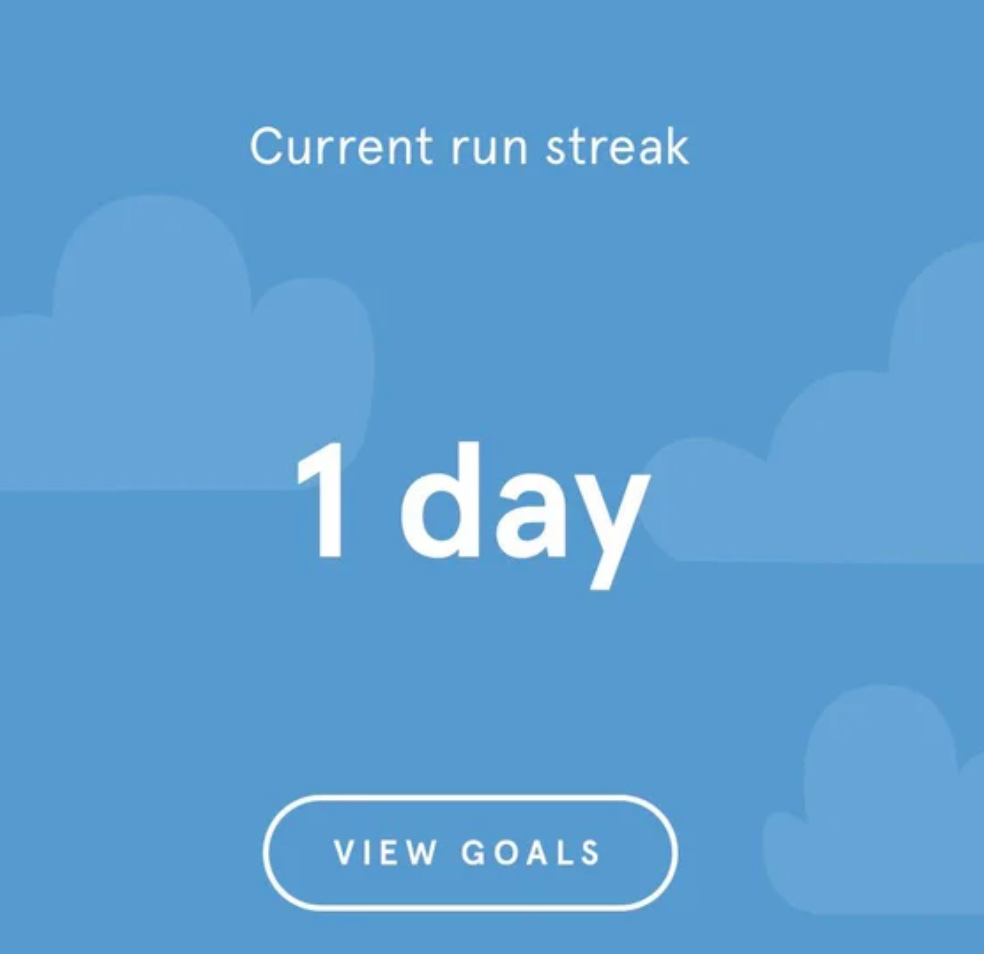

When I started my headspace mindfulness journey, I realized there was a considerable gap between starting a mindfulness practice and actually feeling it’s benefits, and the headspace streak feature drove me to meditate consistently for about 20 days. I was motivated to maintain my streak and “level up,” so to speak.

Behavioural change theory says that my intrinsic motivation to meditate would be bolstered because I would be experiencing the benefits of mindfulness as I maintain a practice.

Instead, my dread of losing a streak increased. I didn’t want to miss the opportunity to hit a daily milestone. I started meditating to avoid breaking my streak.

I was extrinsically motivated and started to engage with the app on a superficial level every day. The goal of mindfulness was replaced by wanting to preserve a streak.

What happened when I missed a login day and broke my heard earned streak? Anger and resentment which ultimately led me to delete the app.

Was I alone in feeling this?

No, I wasn’t.

In the limited number of studies conducted on “gamifying” digital health, I found similar frustrations echoed by patients trialling the “heart game,” a tele-rehabilitation program for heart patients suffering from myocardial infarctions (heart attacks) and hypertension. The game used points and levels as a way to get the patients to complete tasks and exercises.

But the researchers quickly found patients felt frustrated and then defeated when they couldn’t “level up” because the tasks were too hard.

And here’s the critical challenge. Getting the balance right with gamification in healthcare is really, really hard.

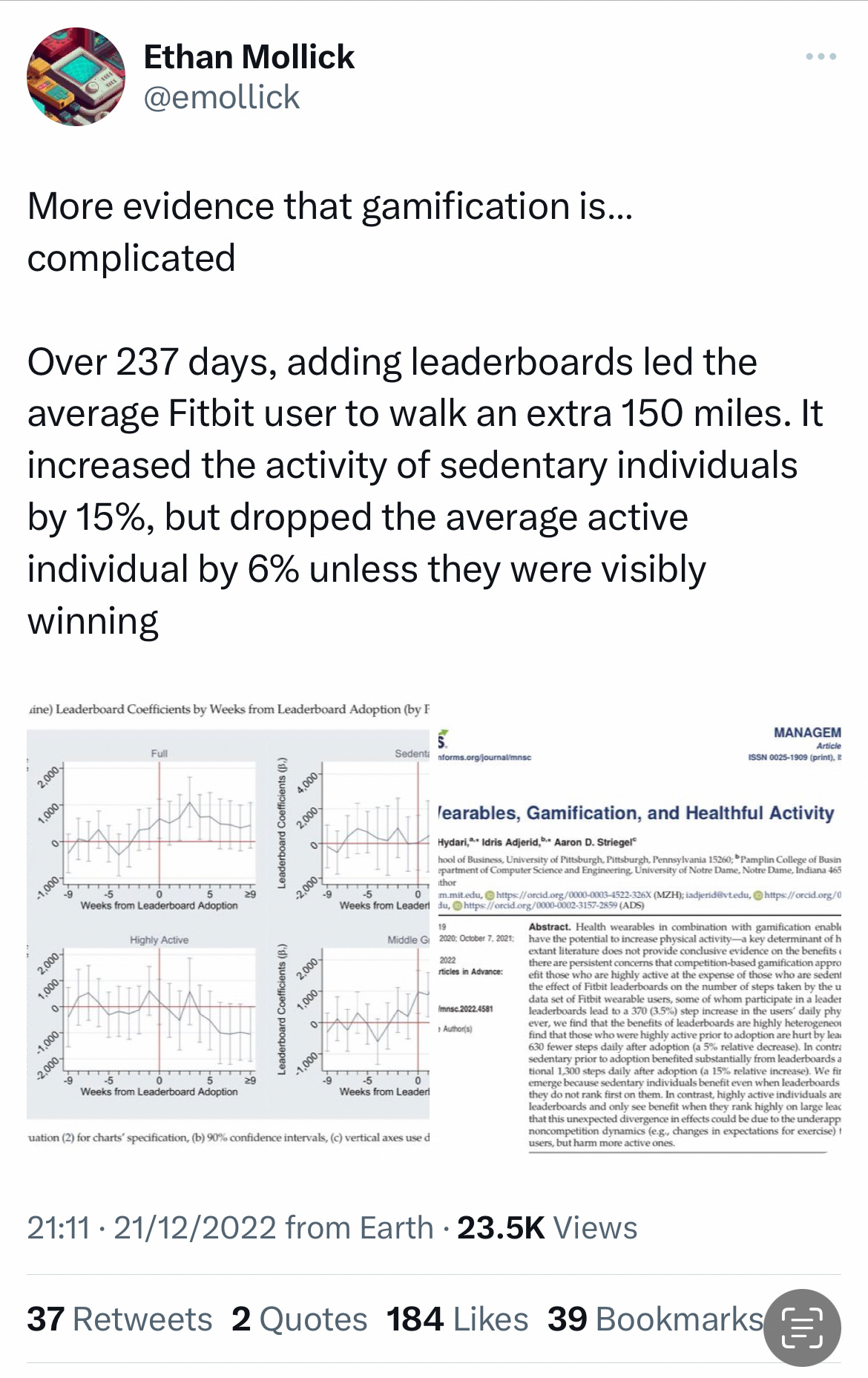

Even popular fitness apps like Fitbit, which boasts a user base of 31 million people, have come under criticism for their gamification techniques.

Critics have argued that Fitbit overemphasizes competition between users through features like leaderboards and challenges which, again, leads to frustration, dejection and ultimately, giving up.

Even the app's use of rewards and badges for achieving milestones seems to be more about maintaining activity on the app itself rather than encouraging users to exercise for its own sake.

As a result, Google recently announced they’re scrapping these gamification principles on Fitbit.

And while I support a full reevaluation of these techniques, I don’t want to throw the baby out with the bath water.

The great dopamine chase

Just because some gamification methods in digital health apps might lead users away from the intended benefits doesn’t mean we should disregard all of them.

Lots of people find the gamified elements fun and engaging and might genuinely change their health behaviours, even if it’s just for the short term.

An important meta analysis of RCT’s exploring the impact of gamification on physical activity and sedentary behaviour did find that gamified interventions had a tangible impact on encouraging individuals to be more active.

The big caveat is that these interventions worked well in the short term, but the effects were considerably weaker after the intervention ended and individuals were followed up.

And that’s the issue.

Gamification works well in the short term. The extrinsic motivation is really high.

But converting this into intrinsic motivation, the stuff that genuinely changes health behaviours seems to be the alchemy we’re missing here.

My biggest fear is that we see over-gamified digital health apps that keep user engagement sky-high without having any health benefits whatsoever. In other words, the addiction economy seeps in and users are left chasing dopamine under the pretext of becoming healthier.

Just think about whether Duolingo can help you speak a language, even if you spend 3000 days maintaining a streak on the app? (hint, the answer is no).

Game on or off?

Ultimately, the goal shouldn’t be to 'win' the game of health. True healthy living is more than just collecting awards, badges, and points. It’s about making conscious decisions for our well-being, without our natural human desires and tendencies being exploited for the sake of user engagement. If my brief stint with mindfulness taught me anything, it’s that no one is keeping score.

Good article. I also think it would be great to know about your opinion regarding gamification in medical education, where the risking patient safety is less. I think gamification is used or in development in terms of simulation in case of medical devices training.

very astute observation… is the Apple Watch really a device for enslavement? kinda…